After the CNN Heroes Program in July, 2008, Dave Schweidenback received this email.

|

After the CNN Heroes Program in July, 2008, Dave Schweidenback received this email.

|

by Dave Schweidenback

Spring 2008 InGear

There is no sleek air-conditioned tube when you disembark from the jet at the Tema airport. Rather, you walk down a set of circa-1950 mobile stairs to the hot tarmac, and you instantly realize you’re in a third world country as the pungent smell of wood-fuel cooking stoves assaults your nose. The airport was bedecked with the red, yellow and green Ghanaian flags to celebrate Ghana’s hosting the 2008 Africa Cup Football tournament. And in the distance, what looked like a thick fog was limiting visibility. It was the time of “harmattan”, when dry winds from the Mediterranean envelope Ghana in a shroud of dust picked up during a 1,500-mile journey across the Sahara.

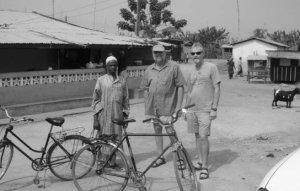

Gary Michel, Pedals for Progress’s Bike Collection Manager and I met our Ghanaian colleague, Kwaku Agyemang, just outside of the terminal and jumped into the taxi waiting to bring us into the city and to WEBike headquarters, our Ghanaian partners. However, our taxi was instantly brought to a crawl as we plunged into totally gridlocked traffic. This is the permanent state of Accra’s roads. At times the capital seems to have more square footage of cars than pavement. And few motorists were obeying traffic rules we take for granted here in the United States.

So it was a relief to escape the congestion of the capital on our third day there and journey into the countryside to meet recipients of the bicycles we’ve shipped to WEBike. As soon as we reached the edge of greater Accra, the perpetual traffic jam disappeared and we had open roads before us.

We were headed to the house of a native herbalist, or healer, Kwaku Osei. Driving along the main paved road to Oda, our driver and the operations manager of WEBike, Ada Annane, suddenly turned onto a red dirt, dusty path leading through the forest. There were no signs and no markings to indicate it was there. Our path not only seemed too small for a car, but it was only drivable because this was the middle of their dry season. Four or five miles later the path just ended, and there, a hundred feet ahead, were three mud shacks with thatched palm roofs. This was our destination. This was where Kwaku and his extended family lived.

We were headed to the house of a native herbalist, or healer, Kwaku Osei. Driving along the main paved road to Oda, our driver and the operations manager of WEBike, Ada Annane, suddenly turned onto a red dirt, dusty path leading through the forest. There were no signs and no markings to indicate it was there. Our path not only seemed too small for a car, but it was only drivable because this was the middle of their dry season. Four or five miles later the path just ended, and there, a hundred feet ahead, were three mud shacks with thatched palm roofs. This was our destination. This was where Kwaku and his extended family lived.

The air was thick with the smell of a small still distilling palm wine into a much more potent brew. We sat on crude wooden benches under a palm frond roof in front of Kwaku’s house. On the wall behind him hung a series of talismans that he used for treating locals who sought his healing powers for a variety of ailments. All of the bikes were out in the fields while we were there, which immediately indicated how useful they were. Kwaku confirmed this, saying the bikes had a very positive effect, helping people move more produce to markets, and giving them access to buyers they didn’t have before. But it was quite clear that they needed help maintaining their bikes. As more bikes arrive in Ghana, and specifically in Kwaku’s vicinity, WEBike will train a local mechanic and help establish a local bike repair shop. More bikes are needed to make such a business viable.

Our first day in the countryside ended with a meal of FuFu, which is pounded casava dumplings in a goat stew. Our hosts Kwaku and Ada didn’t believe two white guys from New Jersey would sit and eat this traditional meal with our fingers. And although Gary, a vegetarian, avoided the meat, this turned out to be one of the best meals we had during our entire trip.

The next day, we left Kwaku and drove 200 miles from the coast to the Muslim village of Alajipapa in Ghana’s plateau region. The majority of the inhabitants here are subsistence farmers tending the land of the local king, and sharing the produce with him. This system of sharecropping is still the harsh reality for many of the rural inhabitants of Ghana. Yet it’s also a relatively harmonious arrangement.

It was Friday, the Muslim holy day, and the whole community had just finished their mid-morning prayers. All of the elders came out to greet us. Dressed in their immaculately clean, holy day finery, they were a stark contrast to the poor mud huts, and red clay streets of the village. This was obviously a very poor town, but its people had a tremendous sense of pride and serious hopes for their future. As we discussed their needs and the utility of the bicycles they had received, they said they looked upon bicycles as progress, and were very interested in receiving more. The bikes were making their lives more productive. Like those in Kwaku’s village, here too, the mobility of cycling helps them move much more produce than walking. The bikes they have are used collectively by the adults in the community. Ideally, they’d each have their own bike.

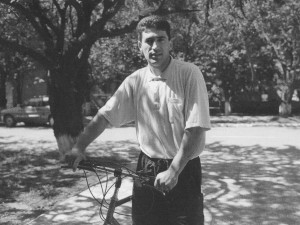

As we moved across the countryside down to Cape Coast and then back inland to Kumasi, the royal city of the Asanti Kings, we made many stops to visit our bicycles and their new owners. One such encounter was in the town of Asuman Kumansu. To get there, we drove through miles of oil palm groves and coco tree orchards—coco production for chocolate is a major cash crop—and arrived at three houses, where luckily, the owner of one of our bicycles was at home. His bike was an immaculate gray Schwinn. I knew it came through our system because there was a sticker on the seat tube advertising Jay’s Bike Shop in Westfield, New Jersey. As they do every year, the Westfield Rotary Club held a bike collection last September. Did the original owner of this bike ever imagine it would become the major means of transportation for a poor family in the middle of the Asanti highlands of Ghana?

As we moved across the countryside down to Cape Coast and then back inland to Kumasi, the royal city of the Asanti Kings, we made many stops to visit our bicycles and their new owners. One such encounter was in the town of Asuman Kumansu. To get there, we drove through miles of oil palm groves and coco tree orchards—coco production for chocolate is a major cash crop—and arrived at three houses, where luckily, the owner of one of our bicycles was at home. His bike was an immaculate gray Schwinn. I knew it came through our system because there was a sticker on the seat tube advertising Jay’s Bike Shop in Westfield, New Jersey. As they do every year, the Westfield Rotary Club held a bike collection last September. Did the original owner of this bike ever imagine it would become the major means of transportation for a poor family in the middle of the Asanti highlands of Ghana?

For me this is what Pedals for Progress represents. We are the link between donors in the United States who want to help the poor of the developing world. Seeing the sticker for Jay’s Bike Shop brought that idea home to me loud and clear. Whoever donated that bike with the hope of changing someone’s life for the better did exactly that. And I was looking at the proof.

Spring 2008 InGear

A little over ten years ago, John Elias, a Peace Corps alum who had been stationed in Jamaica, ran several collections for Pedals for Progress in his hometown in the Colorado Rockies. Doing so nearly crowded himself out of his auto repair business. Storing large numbers of bikes is one of the hazards of recycling used bikes. Since then, John has been a steady contributor to us and a friend of the organization. So, when we had the opportunity to launch a new program in Ewarton, Jamaica, John’s hometown when he was in the Peace Corps, we didn’t hesitate to call on him to help the process. And we’re grateful that he obliged. With John’s help, we were able to get this program on board.

Fall 2007 InGear

In late spring, P4P was contacted by Airline Ambassadors. They were looking for sewing machines to send to their charity program in El Salvador. Airline Ambassadors International is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization affiliated with the United Nations and recognized by the U.S. Congress. It began as a network of airline employees using their pass privileges to help others and expanded into a network of students, medical professionals, families and retirees who volunteer as “Ambassadors of Goodwill” in their home communities and abroad. Members share their skills and talents to care for others and bring compassion into action.

By mid-July, P4P delivered a pick-up truck full of sewing machines to the American Airlines Cargo Terminal at Newark Airport. They were delivered later that week to a Kiwanis Village in San Salvador, El Salvador, where 25 women will train as seamstresses, and upon completion of the course keep their machines.

This fall, we will deliver another 30 machines to El Salvador with Airline Ambassadors. This is an efficient and effective way for our sewing machines to get to the people that really need them. We were fortunate to find such a great synergy with a partner. To learn more about the Airline Ambassadors, visit them at airlineamb.org.

Fall 2007 InGear

One of the difficulties in establishing any new program overseas is getting that first shipment there. Customs, politics, cultures, languages, international trade laws, and even weather can make for a trying experience in getting a shipping container filled with 450 to 500 bikes to a destination hundreds or even thousands of miles away. In trying to get our first shipment to Jamaica, people wanted the bikes, but local politics and Hurricane Dean caused significant delays.

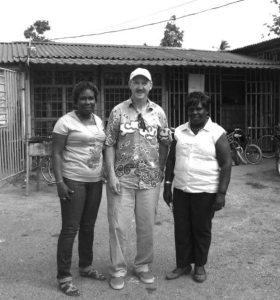

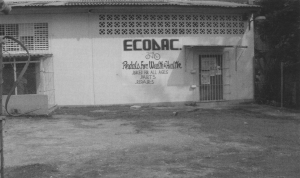

We had been trying for many years to establish a program in Jamaica. Finally, in August of this year, we shipped our first container to our new partner organization, ECODAC, in Ewarton, Jamaica. As with many of our partner organizations, the first shipment will establish a bike shop. But in this case, it will also be a shop that students use for business training. So, not only will bikes serve the local community by providing clean, affordable, reliable transportation, but these bikes will create a business, a business education model, and a training ground for bicycle mechanics. That’s really getting the most out of P4P bicycles.

We had been trying for many years to establish a program in Jamaica. Finally, in August of this year, we shipped our first container to our new partner organization, ECODAC, in Ewarton, Jamaica. As with many of our partner organizations, the first shipment will establish a bike shop. But in this case, it will also be a shop that students use for business training. So, not only will bikes serve the local community by providing clean, affordable, reliable transportation, but these bikes will create a business, a business education model, and a training ground for bicycle mechanics. That’s really getting the most out of P4P bicycles.

Ewarton is a rural community with no public transportation system. Taxis exist, but the fares have continually increased to the point where most people can no longer afford them. So walking is the primary means of mobility. Bikes from Pedals for Progress will change this and significantly improve the lives of many Ewartons. And now that they received their first shipment, the following ones will be much easier to deliver. And Ewarton will soon have many more citizens pedaling instead of walking.

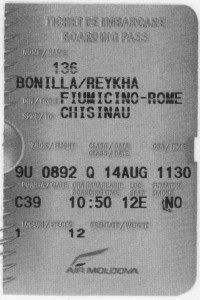

by Reykha Bonilla

Fall 2007 InGear

After many a raised eyebrow from friends, family, and even the travel agent who booked my ticket when I said I wanted to go to Moldova, I always found myself explaining why I was going there. And then I also ended up explaining where “there” was. Located in Eastern Europe surrounded by Romania and the Ukraine, Moldova is a small, landlocked country about the size of Maryland with a population of 4 million people. It was once a major agricultural producer for the Soviet Union. I headed there on August 13th, 2007, to meet our Moldovan colleagues and see their organization, Rural 21, firsthand.

After many a raised eyebrow from friends, family, and even the travel agent who booked my ticket when I said I wanted to go to Moldova, I always found myself explaining why I was going there. And then I also ended up explaining where “there” was. Located in Eastern Europe surrounded by Romania and the Ukraine, Moldova is a small, landlocked country about the size of Maryland with a population of 4 million people. It was once a major agricultural producer for the Soviet Union. I headed there on August 13th, 2007, to meet our Moldovan colleagues and see their organization, Rural 21, firsthand.

I began the 22-hour trip (11 hours in flight) first flying to Rome, Italy, before arriving the next afternoon in Chisinau (quiche-now) the capital city of Moldova. I was met at the airport there by Andrei Rusanovschi of Rural 21. After communicating only through email over the past two years, I was surprised to find that Andrei was a young man in his 20s, not the older gentleman I pictured for some reason. I was also surprised by his fluency in English as my Romanian is nonexistent.

Leaving the capital, we headed southwest for the town of Stefan Voda, where Rural 21 is located. During the two—hour drive, it was obvious, even with the severe drought this year has brought to Moldova, the worst Since the 1940s, that this country is ideal for farming. On either side of the road were vineyards and endless flat fields of sunflowers, corn, and wheat.

In the early evening, we arrived in Stefan Voda at the Rural 21 office in the center of town. Because director Vitale Rusanovschi, Andrei’s father, is well known—he once worked in the government—and as a result of the work they do, Rural 21 has a significant presence in the community. A small welcoming party greeted me, excited that a P4P representative made the trip to visit their country.

Founded 10 years ago to help where the local and national government wasn’t able to, Rural 21 new comprises an internet café, photography and copying services, and, of course, the bicycle shop. All of these businesses raise money for other community projects, such as a new water system providing 24-hour water service, a new heating system for the Maria Beshu School of Arts, and new sidewalks for the town square.

Since 2001, Rural 21 has received 1,800 bicycles from Pedals for Progress, and sold over 1,500 of them in Stefan Voda and surrounding towns. The heart of the Rural 21 bicycle shop is Slavic and his brother Valeriu, who work out of the basement at the Maria Beshu school building. These resident mechanics are there every step of the way. They unload each container, inventory and stock the warehouse, wash and repair each bicycle with care, and restore them to their original glory. With limited space and tools they have created an excellent workshop. They even fashioned homemade repair stands to make their work easier. Eventually, Valeriu and Slavic want to start a mechanic training program to train young people in bicycle repair, and to pass on their passion for cycling. They are also trying to organize a cycling club in Stefan Voda to generate interest in the sport of cycling.

Rural 21 has an advantage over the local bicycle market because the quality of the P4P bikes they receive is high, and they are able to sell them for a very low cost and still cover their expenses. Slavic and Valeriu find that people will often go to the market first and price the new bicycles, then come to the Rural 21 bike shop and purchase a used bike of better quality for less money. Again and again, we find this is a feature of P4P bikes that our partners really appreciate—when we collect bikes, we make sure they are sturdy, reliable, and have many more years of use left in them.

On other trips that I’ve taken to visit our programs, I always compare the public transportation to bicycles and try to determine what people save by owning a bike. I wasn’t able to do this in Moldova, at least not in Stefan Voda, as there is no local transportation infrastructure. There are buses that go to and from the capital, but there is no way to get from town to town. Thus, bicycles are a necessity. I was told this is largely the case throughout the country and worse in the smaller and more remote villages.

In the course of researching this during my visit I had the opportunity to speak with several bicycle owners who were very excited to share their stories with me.

Victor purchased his bicycle in 2006, and works as a carpenter making doors and windows in Stefan Voda. Instead of the 30 minutes it used to take him to get to work, with his bicycle he’s there in four minutes, and gets more work done in a day, earning more leu, the Moldovan monetary unit.

Sergui, an employee at Rural 21, purchased his bicycle three years ago and has been very happy with it. In order to provide for his family, he also has two other jobs, which makes his bicycle essential. He even purchased a child seat so that he can take his son around easily as well.

At 10-years old, Gabrielle is the youngest volunteer at Rural 21. A budding bike mechanic, she helps out Slavic and Valeriu. In return, she received her own bike and is learning bicycle repair. With her new mobility she can get to the shop in just a few minutes where it used to take her over 20 minutes walking.

Inga is a 17-year-old missionary who travels from town to town and uses her bicycle every day to get to the more remote villages she’d otherwise never visit, sometimes pedaling as many as 20 miles a day.

My generous host during my stay, Renell Pettinnelli, arrived at Stefan Voda in the winter of 2006 and waited all winter to purchase her bicycle. Slavic picked out a bike just for her and repaired it. Now Renell easily gets around town to teach English and work with a group that sets women up in business. And of course, she gets to the market regularly and far more easily.

During my visit I spoke with Andrei and Vitale about expanding Rural 21’s bicycle program to become a wholesaler in Moldova. They’ve been speaking with other community organizations in the northern part of the country that are in need of both bicycles and income-generating activities. Because Rural 21 is in the nearest city to the port of Odessa, they’re in a good position to provide this service, and to share their model of success elsewhere in Moldova.

Before my return, I met with the mayor of Stefan Voda, who is very optimistic about what his office and Rural 21 can accomplish during his four-year term. Unlike a lot of town governments, rather than view an organization like Rural 21 as competition or infringing on his domain, this mayor is very supportive of their work. What’s more, he encourages other mayors and politicians to incorporate bikes into their towns, and he even bought two bikes from Rural 21, one so his daughter can ride to school. The mayor and Vitale have worked closely together for many years and are hoping to work together on a larger scale over the next few years.

My visit to Rural 21 was eye opening and inspiring at once. The majority of my travels have been in Latin America, so Eastern Europe was a new experience for me. There is so much need in this small country that I hope we can expand our program in Stefan Voda, and in so doing, help Rural 21 expand theirs.

Moldova is a country filled with hardworking people who have the same needs and wants as every human being—a good job, food to eat, and a place to live. Happily, I saw firsthand that bicycles from Pedals for Progress are playing a big part in helping the community of Stefan Voda achieve these things. More bikes will simply improve more lives there. And helping Rural 21 to grow will serve to improve even more lives throughout the rest of Moldova.

Summer 2007

Abuelas in Action is a new non-profit looking to solve the problem of unemployment among women in Honduras. Our mission is to empower the low-income women in Honduras to break the cycle of unemployment by providing them access to skilled job training and materials in order to own and operate their own small businesses. Pilot Project: The School Uniform Project

Working off of the Pedals for Progress model, Abuelas in Action will provide interested women’s groups in Honduras with all the materials and training necessary in order to start a small business making school uniforms and selling them in the local market. The women will be required to attend 2 training workshops and will be financially responsible for all subsequent shipments of materials from Abuelas in Action. This ensures that the women will take vested interest in their business.

In order to attend seconday school in Honduras, the students are required to wear a uniform. Many students are unable to afford a new uniform and therefore cannot further their education. Women provided with low-cost fabric will be able to sell a better product at a lower price in the local market, thus enabling more children to attend secondary school.

The pilot School Uniform Project began in July 2007 with the Mujeres de Delicias, a group of women from the village of Delicias, Opatoro, Honduras. Delicias is a remote village in the municipality of Opatoro that is home to 30 families and around 100 children. There are 23 women in the Mujeres de Delicias women’s group and they have been working hard since 2007 to supply uniforms and clothing to the surrounding villages. This summer the Mujeres de Delicias, with the money they raised selling their products, were able to construct their own workshop building as well as a small store.

by David McKay Wilson

Fall 2006 InGear

When the Westchester Cycle Club began planning a used bicycle drive for Pedals for Progress, we hoped to collect 150 bikes. That was enough to fill the truck we rented to deliver them to High Bridge, New Jersey, where Pedals for Progress is based. But then we partnered with several houses of worship, a few community groups, and we knew we’d need to rent a second truck. In fact, we needed every inch of three trucks, including Pedals for Progress’ own box truck, to fit the 543 bikes and 10 sewing machines we collected on April 1, 2006.

None of us could’ve guessed when we first started planning that we’d hold the second largest collection in Pedals for Progress’ 15-year history. It’s a credit to the generous residents in the northern suburbs of New York City, who came in droves with their used bikes and checkbooks. Word of mouth, flyers, and Kenneth Edding’s article of the upcoming event in The Journal News generated lots of publicity. Of course, without all the cheerful volunteers who all came together in the sprawling parking lot behind Memorial United Methodist Church, we’d never have been so successful. They gathered at 8 a.m. that morning brimming with energy even though the weather report called for a 50 percent chance of rain. But Reverend Joe Agne assured us that he’d ordered up an ideal day. Soon, we saw patches of blue in the morning sky, and as the sun peeked through, some happy cardinals sang their sweet songs.

None of us could’ve guessed when we first started planning that we’d hold the second largest collection in Pedals for Progress’ 15-year history. It’s a credit to the generous residents in the northern suburbs of New York City, who came in droves with their used bikes and checkbooks. Word of mouth, flyers, and Kenneth Edding’s article of the upcoming event in The Journal News generated lots of publicity. Of course, without all the cheerful volunteers who all came together in the sprawling parking lot behind Memorial United Methodist Church, we’d never have been so successful. They gathered at 8 a.m. that morning brimming with energy even though the weather report called for a 50 percent chance of rain. But Reverend Joe Agne assured us that he’d ordered up an ideal day. Soon, we saw patches of blue in the morning sky, and as the sun peeked through, some happy cardinals sang their sweet songs.

We didn’t have to wait long to get cranking. Our biggest donor, the Andrus Children’s Center in Yonkers, had delivered 65 bikes ahead of time. An official from the Children’s Center saw the article about the bike collection and called saying she already had bikes. Initially, she didn’t have a way to get them all to our lot in White Plains, nor did she have $650 to cover the $10-per-bike shipping charge. Sure enough, though, she found a local moving company willing to donate a truck to move them. And even though the Westchester Cycle Club already committed $750 to the event, a plea for additional contributions on the Club’s online message board raised $650 more to cover these bikes.

So when we arrived Saturday morning, 65 bikes were waiting to be addressed. That’s when Pedals for Progress CEO Dave Schweidenback, in his bright orange T-shirt and white bandanna, gave us all a quick lesson in how to process bikes for shipment: remove the pedals and Zip-tie them to the frame, loosen the stem bolts and turn the handlebars parallel to the frame, lube the chain. Once we got started, our first truck arrived with 25 bikes from Camp Olmstead in Cornwall-on-Hudson. This truck also held another 30 that a Westchester Cycle Club member had in her garage. These were donated by members of her synagogue and local school PTA. And we had to make a second trip to her house to retrieve 40 more bikes, including 20 donated by a local police department, which had cleaned out a storage room crammed with abandoned bikes. The PBA also kicked in $200 to help cover shipping costs.

So when we arrived Saturday morning, 65 bikes were waiting to be addressed. That’s when Pedals for Progress CEO Dave Schweidenback, in his bright orange T-shirt and white bandanna, gave us all a quick lesson in how to process bikes for shipment: remove the pedals and Zip-tie them to the frame, loosen the stem bolts and turn the handlebars parallel to the frame, lube the chain. Once we got started, our first truck arrived with 25 bikes from Camp Olmstead in Cornwall-on-Hudson. This truck also held another 30 that a Westchester Cycle Club member had in her garage. These were donated by members of her synagogue and local school PTA. And we had to make a second trip to her house to retrieve 40 more bikes, including 20 donated by a local police department, which had cleaned out a storage room crammed with abandoned bikes. The PBA also kicked in $200 to help cover shipping costs.

Finally, Dave Schweidenback provided a valuable lesson in packing a truck to the gills with bikes. Bikes were put in side-by-side alternating front wheel forward then rear wheel forward. With the handlebars turned parallel to the frames, the bikes were flat enough to fit about 15 in the width of the truck. Once a row was complete a sheet of plywood was laid on top of the bikes and another row was stacked on top of the first. When all was done and loaded, the trucks were packed so tight there was barely enough space left to fit the buckets of tools.

As we worked on filling the last truck, Reverend Agne’s weather guarantee dissolved in a deluge that soaked the volunteers in a surprisingly warm spring rain. No matter. We filled the truck, and by 1:45 p.m., our second team of drivers was on their way to New Jersey. That’s how we collected, processed, packed and delivered 543 bikes. There had been a job for everyone—a seven-year-old wheeled processed bikes for loading, teens earning community-service credits for high school packed the trucks, and senior citizens loosened pedals and bolts that hadn’t seen a wrench in decades. Finally, at a little after 6:00 p.m., our second truck returned from Jersey concluding a long but satisfying day.

As we worked on filling the last truck, Reverend Agne’s weather guarantee dissolved in a deluge that soaked the volunteers in a surprisingly warm spring rain. No matter. We filled the truck, and by 1:45 p.m., our second team of drivers was on their way to New Jersey. That’s how we collected, processed, packed and delivered 543 bikes. There had been a job for everyone—a seven-year-old wheeled processed bikes for loading, teens earning community-service credits for high school packed the trucks, and senior citizens loosened pedals and bolts that hadn’t seen a wrench in decades. Finally, at a little after 6:00 p.m., our second truck returned from Jersey concluding a long but satisfying day.

In retrospect, it seems like we only touched the surface as we mined our region’s garages and basements for used bikes. We had 245 individuals bring 433 bikes. Three organizations brought an additional 110. Yet thousands of households are within a 20-mile radius of our collection site, and nearly every household has at least one unwanted bike collecting dust in a garage or basement. We just know there are more bikes for Pedals for Progress out there. There has to be. We’ll get those next year.

Fall 2006 InGear

We recently received a letter from Angel describing his experience with our El Salvadoran partner CESTA.

For more information on CESTA’s bicycle program, click here.

Fall 2006 InGear

Lourdes Santiso Salizar took a sewing course at FIDESMA seven years ago. She took the year-long course due to lack of other employment opportunities. After she finished the course at FIDESMA, her parents helped her buy an industrial sewing machine and gave her a workshop space in their home. Today Lourdes runs a successful clothing business in San Andrés de Itzapa, where she custom tailors anything from shirts to wedding gowns. Lourdes now has so much work that she doesn’t even need to advertise her services.